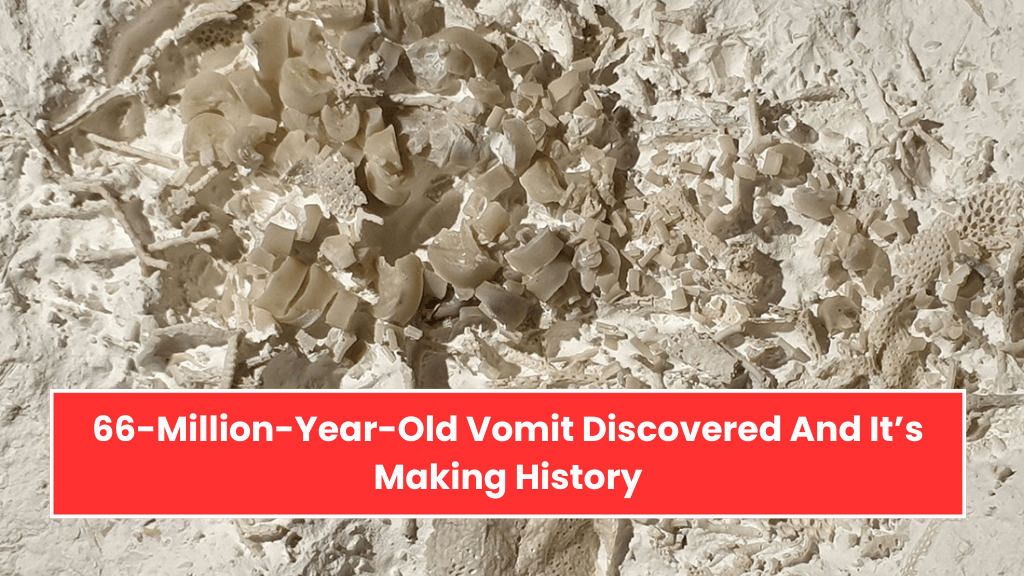

A rare and unusual discovery has been made on the Danish island of Zealand—fossilized vomit dating back 66 million years.

Found by local fossil hunter Peter Bennicke at the Cliffs of Stevns, a UNESCO-listed geological site, the ancient regurgitation contains the remains of sea lilies, a type of marine creature.

This finding sheds new light on predator-prey relationships in the Cretaceous Sea, offering scientists valuable insights into prehistoric ecosystems.

What Was Found?

The fossilized vomit contains two different species of sea lilies, also known as crinoids. John Jagt, a Dutch expert in sea lilies, determined that an ancient predator consumed the creatures but later regurgitated the indigestible skeletal parts.

According to the Museum of East Zealand, this discovery helps researchers better understand the food chains that existed in the Cretaceous Sea.

Jesper Milàn, a Danish paleontologist and curator of geology at Geomuseum Faxe, noted that sea lilies are not particularly nutritious since their bodies consist mainly of calcareous plates held together by minimal soft tissue. He theorized that a fish living in the Cretaceous Sea likely ate the sea lilies before spitting them out.

Significance of the Discovery

The Cliffs of Stevns, where the fossil was found, are renowned for preserving evidence of the Chicxulub meteorite impact, which is widely believed to have caused the mass extinction of dinosaurs about 65 million years ago.

The discovery of the vomit provides new insights into the diet and behavior of marine creatures that lived during this period.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, sea lilies have existed for over 300 million years. Although their diversity has declined, more than 650 species still exist today in marine habitats ranging from coral reefs to deep ocean trenches.

A National Treasure

The fossilized vomit has been classified as “Danekræ,” a designation given to Danish objects of exceptional natural historical value.

Under Danish law, this means the specimen officially belongs to the state rather than its finder, Peter Bennicke. It will be turned over to a natural history museum and displayed at Geomuseum Faxe during the winter holidays.

Milàn called the find “the most famous piece of puke in the world,” and it will now be part of a special exhibition for the public to view.

While vomit is rarely something people admire, this 66-million-year-old fossil has captured the attention of scientists and the public alike.

The discovery offers a rare glimpse into prehistoric marine life and predator-prey interactions in the Cretaceous Sea. As it goes on display in Denmark, visitors will have the chance to view one of the strangest and most scientifically valuable fossils ever found.